Key Takeaways

- Landrace cannabis strains are pure, indigenous varieties that evolved naturally in specific geographic regions over thousands of years

- Modern hybrid cannabis strains resulted from deliberate breeding programs starting primarily in the 1960s-1970s

- The Netherlands played a crucial role in establishing standardized breeding practices and commercializing cannabis genetics

- Recent breeding has focused on CBD content, specific terpene profiles, and specialized medical applications

- Genetic preservation efforts are increasingly important as original landrace varieties face extinction threats

The evolution of cannabis genetics represents one of the most fascinating chapters in botanical history. From pure landrace varieties that evolved naturally over millennia to today’s sophisticated hybrid strains, the journey of cannabis genetics tells a story of human ingenuity, cultural exchange, and scientific advancement.

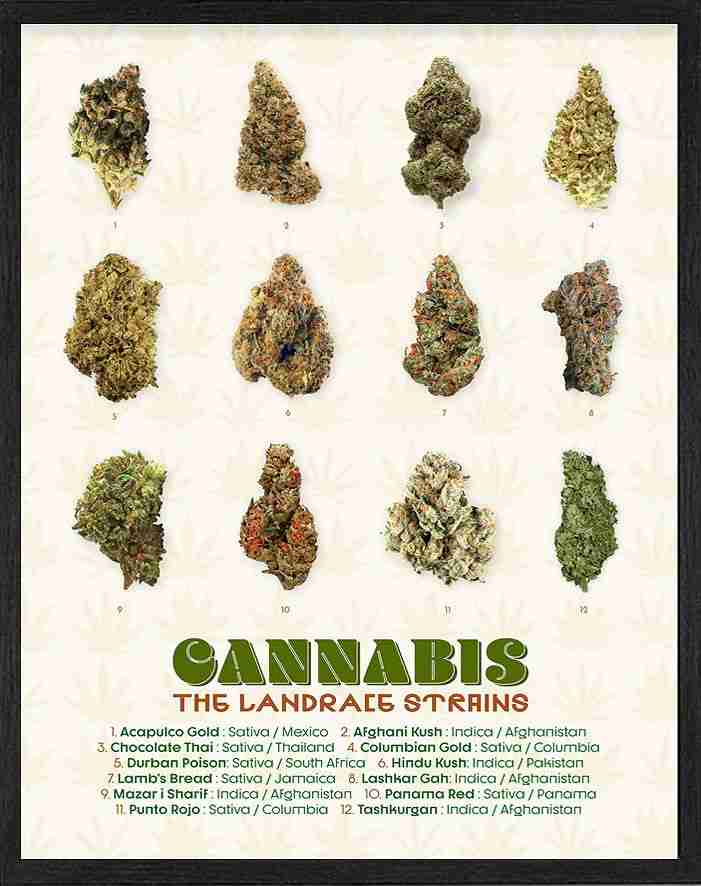

The Origins: Landrace Cannabis Strains

Landrace cannabis strains are the original, naturally-occurring varieties that evolved in specific geographic regions without human intervention. These pure genetic lines adapted to their local environments over thousands of years, developing distinct characteristics based on climate, altitude, and other regional factors.

Key landrace regions include:

- Hindu Kush Mountains (Afghanistan/Pakistan): Home to indica varieties characterized by compact growth, broad leaves, and sedative effects

- Thailand/Laos/Cambodia: Birthplace to energizing sativa varieties with narrow leaves and extended flowering periods

- Jamaica: Home to unique varieties adapted to tropical conditions

- Mexico: Source of sativa strains that would later influence American cannabis culture

- Morocco: Known for hash-producing varieties with resilient characteristics

These landrace strains represent cannabis in its most authentic form—genetically stable populations with consistent traits passed down through natural selection. Before global trade and modern breeding, these distinct genetic pools remained largely isolated from one another.

The First Wave of Hybridization (1960s-1970s)

The modern era of cannabis breeding began when adventurous enthusiasts—often called “strain hunters”—traveled to indigenous growing regions to collect seeds. This period saw the first deliberate crossing of previously isolated genetic lines.

Notable developments during this era:

- Haze: Created in Santa Cruz, California by crossing landrace sativas from Colombia, Mexico, Thailand, and India

- Skunk #1: Developed by Sacred Seeds through selective breeding of Afghan, Mexican, and Colombian varieties

- Northern Lights: Originally bred from Afghan genetics in the Pacific Northwest

These pioneering hybrids combined traits from different landrace varieties, creating new expressions of cannabinoid profiles, terpene production, and growth characteristics. The resulting F1 hybrids demonstrated “hybrid vigor”—enhanced growth rates and yields compared to their parent strains.

The Dutch Revolution (1980s-1990s)

The Netherlands became the epicenter of cannabis breeding innovation thanks to its relatively tolerant laws. Amsterdam’s cannabis coffeeshops created consumer demand for diverse varieties, driving breeders to experiment.

Key developments:

- Establishment of seed companies like Sensi Seeds, Dutch Passion, and Greenhouse Seeds

- Introduction of standardized breeding practices and documentation

- Creation of iconic strains like White Widow, Super Silver Haze, and Jack Herer

- First Cannabis Cup competitions establishing quality standards and driving innovation

Dutch breeders pioneered techniques for stabilizing desirable traits through backcrossing and inbreeding, creating true-breeding lines that would produce consistent offspring. This marked the transition from chance hybridization to methodical breeding programs.

The CBD Renaissance and Medical Breeding (2000s-Present)

The discovery of CBD’s therapeutic potential revolutionized breeding objectives. While early hybrid development focused primarily on THC potency and recreational effects, modern breeding encompasses a broader range of goals.

Recent genetic developments include:

- High-CBD strains like Charlotte’s Web, developed specifically for medical applications

- Balanced THC varieties offering more nuanced effects

- Terpene-focused breeding for specific aromatic profiles and entourage effects

- Autoflowering strains incorporating ruderalis genetics for easier cultivation

- Feminized seed technology eliminating male plants in crops

Today’s breeding programs often utilize genetic testing to identify specific cannabinoid and terpene profiles, allowing for increasingly precise trait selection. Some advanced breeders employ marker-assisted selection to identify desirable genetic traits without waiting for plants to mature.

Historical Timeline of Cannabis Breeding

| Time Period | Key Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1960s | Natural landrace evolution | Distinct regional varieties developing through natural selection |

| 1960s | First collected landrace seeds brought to Western countries | Beginning of intentional cross-breeding |

| 1970s | Creation of first notable hybrids (Skunk #1, Haze) | Foundation for modern cannabis varieties |

| 1976 | Sacred Seeds established in California | First organized breeding program |

| 1983 | First Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam | Established competitive standards for quality |

| 1985 | Founding of Sensi Seeds in Netherlands | Commercialization of cannabis genetics |

| 1990s | Dutch seed banks catalog and standardize genetics | Global distribution of stable hybrid varieties |

| 1996 | California legalizes medical cannabis | Expanded breeding for medical applications |

| 2009 | High-CBD strains identified and isolated | Beginning of CBD-focused breeding |

| 2011 | Charlotte’s Web strain developed | Medical-specific breeding mainstreamed |

| 2018 | U.S. Farm Bill legalizes hemp | Acceleration of industrial hemp breeding |

| 2020s | CRISPR and genomic mapping of cannabis | Beginning of precision genetic breeding |

The Science Behind Modern Cannabis Breeding

Modern cannabis breeding combines traditional agricultural techniques with cutting-edge science:

Phenotype Hunting: Breeders grow multiple seeds from the same cross to identify individuals with optimal expressions of desired traits.

Backcrossing: A selected hybrid is crossed back to one of its parent strains to strengthen specific desired characteristics while maintaining genetic stability.

Polyploidy: Some breeders experiment with chemical treatments to create plants with extra sets of chromosomes, potentially increasing potency and vigor.

Genetic Mapping: Research institutions are sequencing cannabis genomes to better understand the genetic basis for various traits.

The Future of Cannabis Genetics

As legal barriers continue to fall, cannabis breeding is entering an unprecedented era of innovation. Future developments may include:

- CRISPR gene editing to create varieties with specific cannabinoid profiles

- Resurrection of lost landrace genetics through seed preservation efforts

- Development of varieties optimized for different extraction methods

- Tailored medicinal strains targeting specific health conditions

- Industrial hemp varieties with enhanced fiber or seed production capabilities

Preserving Genetic Heritage

As hybridization accelerates, there’s growing concern about landrace preservation. Original landrace varieties represent irreplaceable genetic resources that could hold traits valuable for future breeding programs, especially adaptability to climate change.

Several organizations now focus on collecting and preserving landrace genetics before they disappear due to habitat loss, conflict in native regions, or cross-pollination with introduced varieties.

Conclusion

The journey from landrace to hybrid represents a fascinating intersection of natural evolution and human intervention. Today’s cannabis diversity stems from thousands of years of natural adaptation followed by decades of intentional breeding. As cannabis continues its transition from prohibition to legitimacy, we can expect genetic development to accelerate even further, creating varieties tailored to increasingly specific consumer and industrial needs.

The true power of cannabis genetics lies in this remarkable adaptability—a plant that has evolved alongside humanity for millennia continues to transform to meet our changing needs, representing one of botany’s most dynamic success stories.

Glossary of Cannabis Breeding Terminology

Backcrossing: The process of crossing a hybrid with one of its parent strains to reinforce specific genetic traits.

Chemotype: The chemical profile of a cannabis plant, including its cannabinoid and terpene composition.

Cultivar: A cultivated variety of cannabis with distinct traits that can be maintained through proper breeding.

F1 Hybrid: First-generation cross between two different pure breeding lines.

Feminized Seeds: Seeds genetically engineered to produce only female plants.

Genotype: The genetic makeup of a cannabis plant.

Heterozygous: Containing different alleles of a particular gene or genes.

Homozygous: Containing identical alleles of a particular gene or genes, leading to consistent trait expression.

IBL (Inbred Line): A strain that has been inbred to the point of producing consistent offspring.

Landrace: Naturally occurring, indigenous cannabis variety that has adapted to its local environment.

Phenotype: The observable characteristics of a cannabis plant resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.

Phenohunting: The process of growing multiple plants from the same seed stock to identify individuals with superior traits.

Ruderalis: A cannabis subspecies native to Russia with autoflowering properties.

Stabilizing: The process of breeding for consistency in traits through multiple generations.

Terpenes: Aromatic compounds in cannabis that contribute to each strain’s unique smell, taste, and effects.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between indica and sativa genetics?

Indica and sativa represent the two main subspecies of cannabis. Indica genetics typically originated in mountainous regions like the Hindu Kush, producing plants with broader leaves, shorter stature, and sedative effects. Sativa genetics, originating in equatorial regions, typically produce taller plants with narrower leaves and more energizing effects. Modern hybrids often combine both genetic lineages.

Are landrace strains more potent than modern hybrids?

Generally, no. Modern hybrids have been selectively bred for higher cannabinoid content, particularly THC. Landrace strains typically have more moderate potency but may offer unique terpene profiles and effect balances not found in modern varieties.

Why is preserving landrace genetics important?

Landrace varieties represent irreplaceable genetic diversity developed over thousands of years of natural selection. These genetics may contain valuable traits for disease resistance, climate adaptation, or unique cannabinoid/terpene profiles that could be vital for future breeding programs.

What are autoflowering cannabis genetics?

Autoflowering genetics incorporate DNA from Cannabis ruderalis, a subspecies that flowers based on plant age rather than light cycle changes. This trait allows plants to flower automatically regardless of light schedule, making cultivation easier especially in regions with short growing seasons.

How are feminized seeds created?

Feminized seeds are produced by inducing female plants to produce pollen through chemical treatment or stress techniques. When this female-derived pollen is used to pollinate another female plant, the resulting seeds have two X chromosomes, guaranteeing female offspring nearly 100% of the time.

How has cannabis genomic research advanced breeding?

Genomic research has identified specific genes responsible for cannabinoid production, terpene synthesis, and growth characteristics. This allows breeders to test plants at early growth stages to identify desirable traits without waiting for full maturation, significantly accelerating the breeding process.

References and Further Reading

- Russo, E. B. (2019). The Case for the Entourage Effect and Conventional Breeding of Clinical Cannabis: No “Strain,” No Gain. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9, 1969. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01969

- Clarke, R. C., & Merlin, M. D. (2016). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520292482/cannabis

- Welling, M. T., Liu, L., Raymond, C. A., Ansari, O., & King, G. J. (2019). Developmental Plasticity of the Major Alkyl Cannabinoid Chemotypes in a Diverse Cannabis Genetic Resource Collection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 1635. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01635

- McPartland, J. M. (2018). Cannabis Systematics at the Levels of Family, Genus, and Species. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 3(1), 203-212. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2018.0039

- Grassa, C. J., Wenger, J. P., Dabney, C., Poplawski, S. G., Motley, S. T., Michael, T. P., Schwartz, C. J., & Weiblen, G. D. (2021). A complete Cannabis chromosome assembly and adaptive admixture for elevated cannabidiol (CBD) content. BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/458083

- Small, E., & Cronquist, A. (1976). A practical and natural taxonomy for Cannabis. Taxon, 25(4), 405-435. https://doi.org/10.2307/1220524

- Journal of the International Hemp Association. (Various issues). Historical documentation of breeding programs. http://www.internationalhempassociation.org/

- Sawler, J., Stout, J. M., Gardner, K. M., Hudson, D., Vidmar, J., Butler, L., Page, J. E., & Myles, S. (2015). The Genetic Structure of Marijuana and Hemp. PLOS ONE, 10(8), e0133292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133292